Pico Iyer escribe sobre Mallick

Encuentro un texto de unos de los autores q mas me intrigan, el hindu-californiano-nipon Pico Iyer, acerca de Terence Mallick. Aquí van trozos...

The Promise of Beauty

Terrence Malick’s brave new worlds

by Pico Iyer

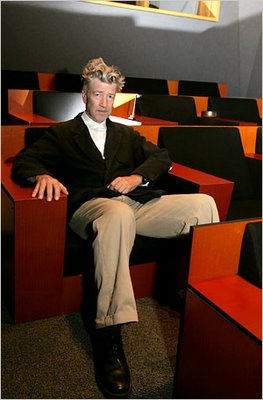

The very notion of a man who translated Martin Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons into English being allowed to film mega-budget Hollywood movies starring George Clooney, John Travolta, and Colin Farrell is enough to make some of us believe there’s justice of some rough kind in the world...

In the thirty-three years since, Malick has made exactly three more movies and given not a single interview. Around such a man, the Thomas Pynchon of the modern cinema, rumours inevitably cluster...

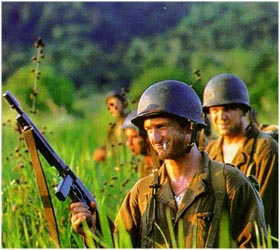

In an industry where the important thing is to keep your name and face in the news, Malick went twenty years between his majestic second film, Days of Heaven, in 1978, and his third, The Thin Red Line, a brooding meditation on the idea that “We’re dirt” and “We’re meat.” The actors who work with him are always asked to comment on the mystery surrounding him, and tend to use words like “very, very shy” and “a very gentle spirit.” Nick Nolte grumbled that all Malick was interested in was light—and indeed, unbeknownst to the studio, he filmed the whole of The Thin Red Line in “the magic hour” of dusk.

...A few weeks after revisiting The New World, I went to see Sigur Rós, the Icelandic post-rock band, play in Osaka. Many of the band’s songs are in a made-up language called Hopelandic, and therefore bypass the realm of words and sense entirely, to speak to something deeper. From the first chords—the band’s four members silhouetted behind a gauzy white curtain, just shadows playing notes—I realized I was in a different, rarely visited part of myself. The mind was stilled and something else was awakened, in heart and even soul. Tears came as when we see a home we never quite knew we had. A lofty claim, perhaps, but one that began to explain to me what Malick is about and how he affects a few of us in ways we can barely articulate. He offers us a way out of the increasingly claustrophobic moment, and into something that feels less passing. Light and words and the natural world all point to a grander silence.

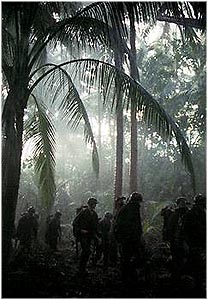

We are all a part of nature, Malick tells us over and over again, feral and vicious and just occasionally unfallen; we are like ellipses in a sentence that some larger force is completing. People in his films are indistinguishable from the creatures, the elements all around them: they are figures moving through grass taller than themselves, silent outlines seen semaphoring in the distance, scarecrows in a landscape that pulses like a living web all around them. We hunger for more, though; we connive, and hatch designs to increase our standing in the world. And as soon as we attempt to rise above our station, to disrupt the larger pattern, we are lost (or exiled from paradise) forever. Hubris, as the Greeks called it: an inability or refusal to live with what we’ve been given. We hunger for Eden, or a greater part of Eden, and so lose the Garden entirely.

The mystic’s gamble is a ruthless one: in return for letting him carry us out of the everyday scheme of things, he will show us the web that lies above and behind us, the ocean into which we dissolve as drops. We live on two levels at once, the Dalai Lama says in The Universe in a Single Atom, and the mystic’s aim is to take us out of “conventional reality,” all event and personality and chatter, into silence and space, the hidden plotting of “ultimate reality.” Malick’s post-human movies offer us none of the consolations of daily life, none of the solace even of morality; they bring us simply, as in Dante or Melville, to the landscape of the soul.

“Who are you Who are you” each of the three lovers in The New World asks, and the voices that keep overlapping on the soundtrack begin to suggest the voices in our heads, as we play out, each one of us, the almost daily struggle between the angels and the beasts in us. “What do you dream of” Pocahontas’s new English husband asks her, as if concerned only with essentials. “I like grass,” she says, much as Linda Manz did in Days of Heaven, and, if those not won over to the Malick universe will say that Pocahontas is just stoned, those who sign on for his adventure will see her response as the right—the natural—answer. As in Sigur Rós again, the sense of voices all around, not always meaning something, takes us into the realm of dream.

...Beauty will lift the soul into the heavens: that is the impenitent, almost sacrilegious promise of a Terrence Malick film. Many, many movies these days are beautiful—more and more—but in no others that I’ve seen is beauty used as an actual promise, a force, almost a main character. Few other films dare to try to invoke a presence of the divine so strong that beauty seems its instrument. Malick’s aim is to take us back to the time when man and what’s beyond man had a contract—the world of Mozart or the Renaissance painter—and he humbles me, shakes my heart with his cathedrals of light through the trees. Then he makes my tears real and deep with the philosophical weight that lies behind his images, the insistent questions about how we get back to “those other shores, the blue hills.”

He cracks me open, in fact, in ways that make other films of the day seem very small. Instead of characters he gives us fire, water, soil, and sky, and instead of dialogue he gives us a perpetual dusk, grunts scrounging to the sound of the final movement of Fauré’s Requiem, In Paradisum. It is as if in film—just the play of light, a scan across a lake, a wolf suddenly appearing at the crest of a moonlit hill—he finds an ancestral form that rhymes with the very promise that first brought pilgrims to America. Malick is the best hope we’ve got, I find myself believing, because hope, the best in us, is what keeps dogging and haunting those savages, in the light.

Pico Iyer is the author, most recently, of Abandon, an Islamic romance, and of Sun After Dark, a collection of essays.