el futuro es digital....

esto salio en Time, en marzo, pero recién me topé con él. Hasta hace unos meses, yo era totalmente análogo. Quería que PERDIDO fuera en 35mm. Pero ahora no. Aunque costara más, lo que las nva cámaras de HD pueden hacer con la noche me tienen asombrado. Y agradecido. A la espera de la nueva de Michael Mann, aqui va este articulo revelador.

Cinema’s Future is Digital not Film

In the digital era, is film dead? As audiences gravitate to DVDs, Hollywood wonders if the movie theater can survive. The rebels are surging. Can the Empire strike back?

By RICHARD CORLISS

Digital is cheep. Film is expensive.

It’s that simple fact that is gobbling up film, chewing it full of its life, and spitting it out in pixilated files. It’s driving the film industry into the depths of the digital domain; an inevitable step that will destroy the romantic movie-going experience that audiences have loved for a century.

I completely understand the seductive lure of digital cinema. Let’s face it; it’s easy and affordable. Anybody today can pick up a Mini DV camcorder for as low as $200. And, anyone can edit their movies on a basic Mac or PC. And, with DVD Rewriters now coming standard, anyone can publish their movie to DVD ready watch on their home theater. It’s no mystery that times have certainly changed.

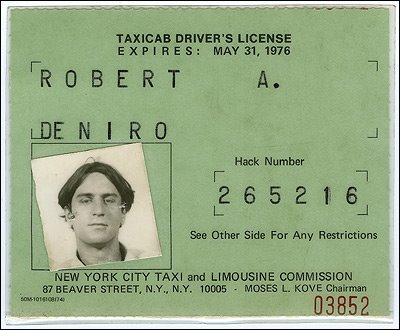

Looking back to the 1970’s, when film was revolutionized by the decade’s “rebel filmmakers”, directors, like the legendary Martin Scorsese, found it extraordinarily difficult to find work when starting out. You had to prove you could do the job. Film is expensive, you just don’t hand over a film project to anyone; there’s a risk. Charlie Kaufman, screenwriter of Being John Malkovich and Adaptation, talks about that very risk that gives cinema its emotional power:

“I’m not interested in watching films right now that feel like a product. I want to feel like I’m watching something that’s really really a mess. Does this make any sense? I don’t know what it is, I want to watch a film in which it feels like there’s something at risk, that’s not a package. But everything seems to be a package. I’m on edge, I don’t want to feel like someone’s sort of presenting me with something and I’m supposed to appreciate it… It’s just watching a marketing machine, and there’s something very ugly about that. I hate it, I think it’s crap. It’s marketing, and marketing is marketing.”

Digital cinema eliminates much of the cost and risk normally involved with 35mm film. From a business standpoint, it’s a no-brainer; the less you risk, the less you lose. However, film enthusiasts will tell you that it’s the risk that makes film such a powerful art form. If you’re making a film, you have thousands or millions of dollars riding on the notion, that, you, as a filmmaker, are going to bring that money back in the box-office. When you have so much riding on your shoulders, you make sure the work you put out is the very best work you could have done under the circumstances; your very career depends on it.

The problem is the studios don’t want to make films that directors need to pull-off. But, as everyone knows, when a group of filmmakers “pull-off” a film, it’s one of the most powerful and emotional experiences in all of cinema.

Look back to 1977, the year George Lucas’ Star Wars changed cinema forever. Everyone knows the story; the finances, the time restraints, the special effects. The set was a mess of feuds and miscommunication. No one had ever done anything like that before. It was a film that Lucas and his team needed to “pull-off”… and they did. The risk was huge, but the pay-off was much greater.

Look at a few other films; The Godfather, The Lord of the Rings trilogy. In both situations, the risks were enormous and the filmmakers were under enormous amounts of stress and pressure. I don’t need to explain the stories. We all know them; they’ve become synonymous with the great American “rags to riches” tales of our time.

I’m not saying that digital eliminates all the risk involved with film; it doesn’t. However, implementing digital into cinema is just another way for studios to ensure quantity over quality. To make the concept simple, take a look at what photography has become. With digital photography, a consumer is given countless pictures to take. Nothing is premeditated; take as many pictures as you want, it doesn’t matter. With a film camera, you have 24 pictures; that’s it. So, you better make absolutely sure you think about shooting before you shoot, because you can’t delete. That is where skill is developed.

It’s skill like that that can’t be developed using digital as a medium. Not saying that there isn’t skill in digital cinema, there is, but it’s different skill. That’s the main idea here; that film and digital are two completely different mediums. Neither being “better” than the other, just different. It’s like comparing Broadway to Hollywood; you can’t.

The same applies to the way we view cinema. Theater attendance has been descending; and for obvious reasons. Let’s say you’re going to take you’re girl to the movies on a Friday night. The average cost of a ticket is about $8, so, just getting in costs you $16. Now you want something to eat while you sit for two hours. The average price for two soft drinks and a large popcorn will cost you anywhere from $10 to $12. So, when we add it all together, you’re paying anywhere from $26 to $28 for a night at the movies. That’s pretty expensive since you can own the film on DVD for about $14 and not have to deal with broken seats, kids crying, people talking, sticking floors, speakers going in and out, or the picture out of focus.

People are talking about the end of the movie theater. With films like Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble, having its theatrical release and DVD release on the same day, we’re seeing a new marketing wave sweeping Hollywood. Imagine getting a live feed straight to your iPod or computer the minute a film releases. Such technologies are being considered.

However, most filmmakers are completely against some of those technologies, such as Steven Spielberg:

“Mr Spielberg shudders at the notion of atomised viewers calling up a film on their laptops at the touch of a button, home and alone. A romantic, as his pet cinematic themes of fantasy, escapism, discovery and redemption show, Mr Spielberg prefers the idea of strangers huddled together in the dark, watching a flickering image on the screen.”

“‘I only paint on the one size sheet of paper,’ Spielberg says. ‘I make my movies for a movie theater, and I like to imagine how big that screen is. But I also realize on a laptop on an airplane or, even worse, on an iPod, they are never going to see that character, and an element of the story will be lost.’”

If digital cinema takes over the film industry, much of the magic of films will be lost. What we need to understand, is that film and digital are two different mediums. They need to coexist together; not allowing one to over-power the other.

If film is lost, an important element of our history and culture is also lost. Film is unique, for better or for worse. It may be old technology, but so is the internal combustion engine, and you can’t get a man who loves cars to use anything else.

Here's a magic glimpse into the future of movies. A big blockbuster opens. Some people see it in sparkling digital clarity on wraparound screens in ultraswank theaters; others watch the same movie the same day on an 8-ft.-wide screen in their home media center; still others get it transmitted instantly through their computer, iPod or cell phone. It's a looking-glass scenario that could happen in a future near you--if the people who finance and exhibit Hollywood movies want it to.

On Oscar night last week, though, the looking glass was not a crystal ball but a rearview mirror. Hollywood's gentry celebrated the past--the misty history of cinema, evoked with montages of ancient genres and deceased artistes. From the films honored, you would hardly have noticed that under the academy members' smartly shod feet, a seismic shift was taking place.

We are at the bright dawn of the movies' digital age, but the Hollywood establishment still has its shades drawn. In the Oscar show at the Kodak Theatre (named after a company that is crucially invested in the film-stock status quo), the most popular live-action digital movie in history, George Lucas' Star Wars: Episode III--Revenge of the Sith, won no awards, not even one for technical achievement. The year's boldest, most innovative digital experiment, Robert Rodriguez and Frank Miller's Sin City, got no nominations at all.

The Oscar revelers seemed unaware that movies have two big problems: the way they're made and the way they're shown.

It has often been noted that if Henry Ford were to come back today, he would wonder why no one had come up with a better idea than the internal combustion engine. A similar thought may occur to any visitor to a movie shoot. Dozens, maybe hundreds of technicians adjust the lights, apply the makeup and dress the set, much the way it was done almost 100 years ago. And as in D.W. Griffith's day, the film still runs through a camera, then is processed, reproduced many times and sent to theaters.

The addiction to doing things that way baffles Lucas. "Do you still use a typewriter?" he asks a TIME movie critic. "Do you go to a library and consult books for most of your research? Is your story set in type, letter by letter? No. Your business takes advantage of technological advances. Why shouldn't my business?"

Well, for one thing, say the movie atavists, film has a more human texture, an emotional weight. "Digital is just too smooth," says M. Night Shyamalan, writer-director of The Sixth Sense and a defender of the film tradition. "You almost have to degrade the image to make it more real. If you take a digital photo and I take one on film, there's just no way you're going to compete with the humanity that I can create from my little Hasselblad. Yours will be smoother, crisper, perfect in every way, and mine will be grainy, but you would definitely grab my picture over the digital one."

Directors who have worked in digital don't agree. They say it's capable of a chromatic subtlety that film can't match. Michael Mann, whose 2004 Collateral was, he says, "the first photo-real use of digital," is using the same process to shoot the big-screen version of his old Miami Vice TV series. "In the nightscapes in Collateral, you're seeing buildings a mile away. You're seeing clouds in the sky four or five miles away. On film that would all just be black."

What Mann pioneered is now a trend. "When we shot Collateral, we were one of the first," he says. "This year there were about 25 films shooting digitally." That number is bound to mushroom as young directors, whose computers were their boyhood buddies and who have no nostalgic attachment to film, come to the fore.

One is Rodriguez, 37, the Lone Star maverick who writes, directs, shoots, cuts and scores his own movies as well as supervises the special effects, doing it all at his home ranch on the Pedernales River and at a small Austin, Texas, studio. Using high-definition cameras, he shot his Sin City actors against a green screen, filling in the backgrounds digitally, and rarely went beyond a second or third take. That's one secret to making a gorgeous all-star movie for $40 million--less than half the average Hollywood budget.

It was Lucas who turned Rodriguez on to digital after a visit to the elder's Skywalker Ranch more than five years ago. All Lucas had done was perfect the modern blockbuster and create the first major special-effects company (ILM) and the first digital-animation outfit (which became Pixar). He changed the way movies were made and marketed. Now the richest, most influential maker of movies had found in Rodriguez an apt pupil, another "regional" filmmaker who could buck the system.

In one aspect of moviemaking--crew size--Rodriguez has outstripped Lucas. The two most recent Star Wars movies, made digitally, employed as many on-set crew members as did the last filmed episode, The Phantom Menace. (Lucas offers that as an argument that Hollywood technicians need not worry that a switch to digital would put them out of work.) But do-it-himself Rodriguez has a crew that is tiny and tight. "It's nice because you don't have this huge army," he said in 2003. "It's a commando group of people really into the project." Rodriguez loves his outlaw status, boasting, "I'm years ahead. The professionals are not paying attention."

But the independent directors are. Many of them have used digital equipment for years. Steven Soderbergh shot his indie movie Bubble with the same camera, a Sony F950, that Lucas used on Sith and Rodriguez on Sin City. And indie imp-guru Kevin Smith (Clerks, Chasing Amy) notes, "There is a Panasonic camera, the 100, that gives a picture that's about as good-looking as 16-mm or 35-mm film. The kids today who are making their do-it-yourself features are doing it with high-definition video. If I was shooting Clerks today, I'd probably use that camera."

Smith wanted to use a digital camera for Clerks II, the sequel to his 1994 debut hit, but his director of photography didn't feel comfortable with the process. "A lot of directors and directors of photography are resistant to put down what they're familiar with," Smith says. Besides the shock of the new, there's the love of the old. "Most people in film have a great affection for film stock, for the medium. And they feel that moving in a digital direction is kind of leaving their history behind. It's more sentimental than anything else."

If moviemakers won't shoot digitally, they'll edit digitally, citing ease and efficiency. But Steven Spielberg and his longtime editor Michael Kahn don't. "Michael and I are the last persons cutting movies on KEMs," he says, referring to the German flatbed machine that is no longer manufactured. "I still love cutting on film. I just love going into an editing room and smelling the photochemistry and seeing my editor with mini-strands of film around his neck. The greatest films ever made were cut on film, and I'm tenaciously hanging on to the process."

Once a film is shot and cut, it has to be copied, sent to theaters and put on the screen--steps that are expensive and risky. Print quality, for example, can vary drastically from frame to frame and print to print. The quality of projection may also vary. "There are still theaters that run the projector lamp at less than proper brightness," says Mann. (A digital projector is much more accurate.) Finally, film degenerates, the way a vinyl record does under a stylus or a videocassette does with frequent use. "With film you have degradation problems," Smith says, "where the stock starts breaking down. Frames get lost when they cut reels together." The digital look will stay fresh for the life of the theatrical run.

If there's an argument for digital that Hollywood can get behind, it's this: it's far cheaper than film--cheaper to shoot, cut and duplicate. But the big savings come in getting the product to the public. Says Lucas: "Making a big movie, a Harry Potter or a Spider-Man, you're spending $20 [million] to $30 million for the prints just to strike them and ship them to the theaters. Smaller movies have to spend a huge part of their budgets on prints." Digital would cut print and shipping costs about 80%. Even Spielberg, who wears many hats, sees the efficacy of digital. "I may be the last person as a director to accept it," he says, "but I won't be the last person to accept it as someone who runs a film company."

So who doesn't love the new movie deal? Well, some studio chiefs, who are worried that a movie on disc is much easier to dupe, and piracy is a huge drain on their income. But mainly theater owners. When they hear the word digital, they reach for their digitalis. Already feeling the hit from the 13% slump in moviegoing over the past three years, they aren't eager to spend the more than $3 billion or so that it would cost to convert approximately 36,000 film projectors to digital.

"Digital cinema is probably a lot further away than most people would think," says Kurt Hall, president and CEO of National CineMedia, the marketing arm of AMC, Cinemark and Regal Entertainment Group. "There's still a lot of work to be done on the technology, both in making it secure [from piracy] for the content owners and in making sure that the systems work and can be operated efficiently by the theater circuits."

In the late '20s, when talking pictures replaced the silents, theaters converted to sound within two years. But the coming of sound was immediately and immensely popular. Today, although films shown on the giant IMAX screens make money and although computer-made animated features have been spanking the butts of traditional cartoons, there's no conclusive evidence that the billions it would cost to go digital would be repaid by a box-office surge. "Our research shows that the audience generally isn't going to pay more and isn't going to go more," Hall says. "So there's no financial model that creates an incentive for the exhibitor to make this investment."

Lucas has tried for years to be the irresistible force to the exhibitors' immovable object. In 2002, when he released Star Wars: Episode II--Attack of the Clones, he opened it on 63 digital screens in North America, along with the thousands of screens showing the film version, and declared that in three years, when Revenge of the Sith came out, it would play only digitally. He says he even offered the exhibitors a financial incentive: "It costs about $1,200 for a film print and about $200 for a digital print. So what you do is charge the distributor the same $1,200 they would ordinarily be charged, and $1,000 of it goes into a pot that eventually pays for all the projectors and everything. In about five years you would reconvert the entire industry." And who bought in? "No one's bought in yet. But they will. It's just a matter of time." Digital Sith played on 111 screens in the U.S. and Canada--still a tiny slice of the total number of venues.

Lucas and other directors don't subscribe to the cheap-date theory of movie attendance--that kids go to get out of the house, to be with their peers and away from their parents. Directors also ignore the complaints about moviegoing--the glop on the floor, the indifferent projection, the half an hour of ads and in the row behind you a nattering couple rehearsing their Jerry Springer act. No, to directors, moviegoing is an almost religious act: a Mass experience. You walk into a cathedral, feel your spirit soar with hundreds of other communicants and watch the transubstantiation of images into feelings. The audience becomes a community, the movie the Communion.

"A 65-ft.-wide screen and 500 people reacting to the movie--there is nothing like that experience," says Mann. Shyamalan sees it as a mystic conversation. "With enough strangers in the room," he says, "you become part of this collective human soul--which is a much more powerful way to watch a movie" than seeing it alone at home.

But will they still go--if day-and-date distribution comes to pass, that is--when they can buy a DVD the same day and see it with a bunch of friends on a 45-in. screen? Much was made of Soderbergh's experiment with Bubble--a minimalist, low-budget, no-star movie that opened nearly simultaneously in theaters, video stores and homes. And people didn't go for it in any format. Shyamalan sees a lesson there: "Bubble had $10 million worth of free publicity. Bubble had the advantage over any independent movie of its same ilk. It had so many advantages, and still it didn't perform. If Bubble did well, wouldn't that have been evidence that day-and-date works? Well, they tried it, and they failed."

Lucas, who thinks day-and-date is an inevitable step to fight piracy, also believes it won't hurt the box office. Moviegoing, he says, "is like watching a football game. Who in the world would go out in 20-below weather and sit there and watch a football game where you can barely see the players? Football games are on TV, and it doesn't affect stadium attendance at all. It's the same with movies. People who really love movies and like to go out on a Saturday night will go to the movie theater."

Some blame the shrinking theater audience on the narrowing gap between a movie's premiere in theaters and its debut in video stores--from six months a few years ago to about four months or less today. "With the window getting smaller and smaller," says Smith, "people don't want to leave the house. The audience is being trained that they don't have to run out to the theater to see something." For many viewers, especially adults, the kids who see the big blockbusters and the critics who review the little indie films have essentially become focus groups that help them decide whether they should see a movie--when it comes out on DVD.

The genius of late 20th century entrepreneurism was to get people to pay a lot for things they were used to getting cheap (coffee) or free (water). A quarter-century ago, Hollywood made most of its money from showing films in theaters. Now the biggest bucks come from DVDs and pay TV. Producers also got something for nothing by packaging recent and old TV shows for the DVD market. All those revenue streams give folks more reasons to stay home, encased in their all-media cocoons, in some cases chained to the desktop deity that can never get enough attention. Just as the computer helps them do many things that used to take them out--work, shopping, buying books, renting movies--so will it soon allow them to download movies to watch on it. As Smith notes, "It's tough to cram three or four people in front of a computer to watch something. But no doubt Steve Jobs is working on this."

If the Internetting or iPodding of movies does take over, that would be a strange revolution indeed. It's one thing to miniaturize phones and radios for easier use. It's another to reduce the 65-ft. movie-palace dream images of old--the ones revived for last week's Oscar show--onto a screen the size of Dick Tracy's wristwatch.

Directors say they frame a shot with the big--not the small--screen in mind. "I only paint on the one size sheet of paper," Spielberg says. "I make my movies for a movie theater, and I like to imagine how big that screen is. But I also realize on a laptop on an airplane or, even worse, on an iPod, they are never going to see that character, and an element of the story will be lost." Whatever is lost on the smaller screen, DVD has become, in Smith's words, "historically the final record of your movie. That's the one people watch over and over." Rodriguez has said that the "real versions" of his movies are the extended, unrated ones on DVD.

So what can lure us to a movie theater? One thought: better movies! But by better, most directors mean "more sophisticated technically." Because with Star Wars in 1977, Lucas spurred another revolution: the triumph of the special-effecty, kid-friendly fantasy blockbuster. With space-age technique and retro, '40s-serial content, the film made so much money, it seduced the studios and fired the imaginations of directors. "The great thing about computerized effects," says Spielberg, "is that now we can do anything our imaginations tell us." Absolutely--if your imagination runs to dinosaurs and space aliens. And no question, those critters sell tickets. All five of last year's top worldwide grossers were fantasies, and all but one (The Chronicles of Narnia) a sequel or a remake.

In the brave new digital world, form is defining content. Because the toys are so cool, directors make movies to exploit their technical possibilities. That's why James Cameron, after doing Titanic, the all-time top grosser, stopped making feature films to shoot underwater documentaries with his favorite new toy, the 3-D camera. Going back to his old camera, he told ComingSoon.net "just seemed like going back from a car to a bicycle." Battle Angel, his first feature since 1997, will be shown in 3-D. (And yes, with the funny glasses.) Lucas is planning to release all six Star Wars episodes in 3-D as well.

That's one future of movies--IMAX-size extravaganzas you can see only in a movie house. It's a throwback to the Cinerama and CinemaScope the studios used against the first home-viewing medium, TV.

But Shyamalan has an even more radical--or counterrevolutionary--idea. "Let's say you can see any movie you want anytime. You can see it on a phone in the toilet when it opens," he says. "Well, somebody like me is going to go to somebody like Warner Bros. and say, 'I want to make a movie but only for the movie theaters. How much money will you give me to make a movie like that?' And they'll do the math and say, 'We'll give you $20 million.' And someone like me is going to say, 'O.K., I'm in.' Well, one of these someones is going to be successful at it. And people will go see it and fall in love with it and tell everybody, 'Hey, did you see that movie? It's only playing in the movie theaters!' And it's going to be magic."

—With reporting by Desa Philadelphia/Los Angeles, Cathy Booth Thomas/Austin