un gran perfil sobre Michael Mann aparecido en LA WEEKLY...

A Mann's Man's World

Written by SCOTT FOUNDAS

LA WEEKLY

Think you can keep up with the Miami Vice director?

If it is true, as Jean Renoir said, that a director makes only one movie, then Michael Mann makes the one I don’t just want to watch, it’s the one I want to live in.

Perhaps you have seen it: It is the story of the night and the city and the men who inhabit it — professionals to the core who operate on instinct, sometimes living inside the law, but more often indifferent to it. They will meet on rooftops or in desolate industrial expanses to suss out the terrain, plotting their next move, while the low rumble of an electric guitar sounds in the distance. Inevitably, there will come a woman, and with her the momentary illusion of a “normal” life. And just as inevitably, that hoped-for bliss will prove as out of reach as Proust’s dream of fair Albertine. This is not always the story, for Michael Mann has made a historical epic about the French and Indian War (The Last of the Mohicans), a supernatural fable set in the waning days of World War II (The Keep), and a fine, underrated biopic of Muhammad Ali. Yet even those films are finally portraits of solitary men on a mission, the last exponents of some dying way of life. This is as true of Hawkeye the Mohican as it is of the journalist Lowell Bergman, the subject of The Insider (1999), who is willing to sacrifice himself to protect his source. Surely, if Mann had lived at the time of his namesake, director Anthony Mann (no relation), he would have been a master of noirs and Westerns. Now he is the maker of such films reconceived as existential urban tragedies.

What I am describing here is not some adolescent when-men-were-men fantasy (on my part or Mann’s), but rather the sense of profound symbiosis between the content of a film, its form, and the personality of its maker. It’s the feeling that a movie isn’t just telling a story, but expressing a fully realized sensibility about the world and the motives of human behavior. This is the experience you get watching the movies of the directors Mann names as his influences — Dreyer, Murnau, Eisenstein — and of several others he does not mention but whose presence is nonetheless felt: Bresson, Peckinpah and Jean-Pierre Melville. And it is a feeling that courses through Mann’s own work. Few in American movies have delivered more consistently exciting picture shows over these past 25 years, or done so with such relative anonymity. Though he is their contemporary, Mann is not typically mentioned in the same breath as Coppola and Scorsese and the other enfants terribles of the New American Cinema, in part because he did not make his first theatrical feature until 1981. He has only once been nominated for the directing Oscar (for The Insider). And he may be the only major American filmmaker whose greatest popular success thus far has been on television. I am referring, of course, to Miami Vice, the trendsetting 1984-89 series on which Mann served as executive producer and resident stylistic guru. Indeed, if you lived in South Florida in the 1980s, as I did, it was hard to tell whether the show was more influenced by its location or the other way around.

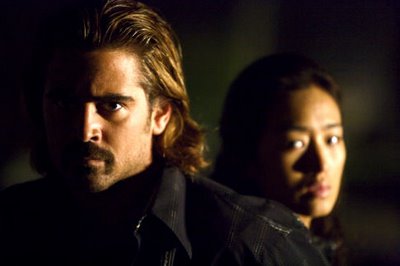

Now Miami Vice is a feature film written and directed by Mann, though a less reverent small-to-big-screen transfer can hardly be imagined. There are no pink flamingos or white linen suits to be found here, and the pastel picture-postcard vistas of the 1980s have given way to steely expanses that are like etchings on metallic plates. Even detectives Sonny Crockett (Colin Farrell) and Ricardo Tubbs (Jamie Foxx) have evolved, as they find themselves confronted with a new generation of kingpins who are to yesterday’s Pablo Escobar what Wal-Mart is to the mom-and-pop corner market. Says Mann: “In a postmodern globalized world, there is no criminal organization locked to a geographical place producing one commodity, like cocaine. Now, if you’re running a transnational criminal organization, you’re a master of tubing, down which anything can move: pirated software, frozen chickens out of Russia, Ecstasy from Holland.”

By Mann’s own admission, the dynamic between the old Vice and the new is “a profound connection and no relationship whatsoever, at one and the same time.” And that suits him just fine, for Michael Mann doesn’t like to repeat himself. “I like change. I don’t like being in the same room for too long,” he says in fast, clipped diction and a flat Chicago accent that’s been little dulled by three decades of living in Los Angeles. “That’s why a two-year period making a movie is perfect for me, and that’s why, after two years, I basically tried to substitute other folks for myself on Miami Vice [the TV show]. I said to myself: ‘I’m here trying to help folks making these little movies — why aren’t I directing?’ So I went off and made Manhunter (1986).”

What drew Mann back, he says, was a combination of factors, starting with the changed landscape of Miami itself. “In 1984, Miami was larger than a small town, but smaller than a small city,” he says. “And sure, at the Mutiny, there were a bunch of wild guys who were making a lot of money every weekend running in loads. But that was then. Now, Miami is way different. It’s more South American than it is Central American; the money is bigger, there’s more of it; and it’s hugely cosmopolitan.”

Moreover, there was the appeal of making a film about undercover police work — a subject left unexamined by Mann’s earlier films about law enforcement officials, career criminals and the often short distance separating the two. “I did some research into people who do very difficult kinds of enhanced undercover work. Really wild stuff — extremely dangerous, long term, some of it outside the country. Stuff that distorts your identity. I thought I knew about undercover — I’d seen Serpico and everything else — but I really hadn’t explored what happens when you go that far undercover.”

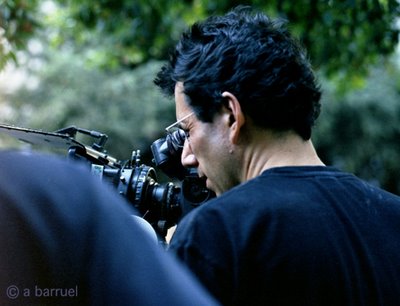

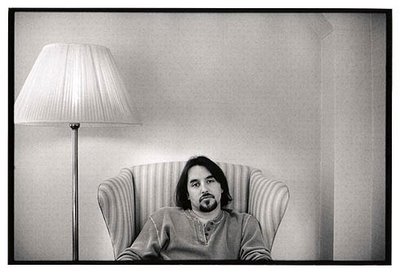

It’s Tuesday morning, 10 days before Miami Vice arrives in theaters, and 24 hours after Mann has completed a grueling four-day press junket. As we talk, he gives me a tour of his expansive Santa Monica offices, oddly depopulated now, but until recently home base for Vice’s post-production. In one room, a bank of blinking and whirring hard drives store some 300 hours of dailies, all shot using the latest generation of high-definition video cameras — the second “film” Mann has made this way, following Collateral in 2004. And there is a screening room powered by a 2K digital projector and a pricey Avid Nitrous computer system, allowing Mann to look at a high-resolution output of the movie on a theater-sized screen, at any stage of the editing process, at any time of the day or night. “We run a 24-hour operation here,” Mann tells me, and it isn’t hard to believe: His reputation as a perfectionist precedes him: On the set, he frequently operates the camera himself. At screenings of his films, he has been known to rope off seats that he feels have an undesirable viewing angle. And right now, he is tape-recording our conversation as well. He is driven and demanding, and he expects nothing less of those who collaborate with him.

“This work is for people who are artistically ambitious,” he says. “This is for people who like challenges. If you want to kick back and take life easy, this is not for you.”

On Vice, in addition to his own exhaustive research, that meant subjecting stars Farrell and Foxx to three months of on-the-job training in Miami, where they worked with local and federal law enforcement officials learning not just how to seem like Crockett and Tubbs, but how to be Crockett and Tubbs. “We ran scenarios. We ran simulations. And they were as close to real reality and lifelike as you can imagine,” says Mann. “We ran loads in from offshore at midnight, in the pitch dark — two boats trying to find each other seven miles out at sea from Miami with no lights, using radio codes and the kind of signals these guys would use on a radio, knowing that stuff may be intercepted, so you’ve got to be talking about something else. And when they were supposed to hit a drop and unload a load, the drop would be blown and they’d have to get to a fallback drop, and when they got to the fallback drop the load would be short: They’re supposed to have 20 kilos and they’ve only got 18. You name it, we did it.”

Mann and I have moved on to his private office — pastel and uncluttered, with sweeping views of the Santa Monica skyline — when we’re interrupted by a cell phone call. It’s Mann’s wife, Summer, asking about a replacement ink cartridge for their home computer printer. The interlude is a powerful corrective to those who might imagine that Mann’s Spartan protagonists are somehow alter-egos or examinations of self: Michael Mann has a wife. Of more than 30 years. Who calls him at work about printer ink. He also has four grown children, including a daughter, Ami, who has followed in her father’s footsteps, writing and directing for TV and the movies. But beyond that, Mann is loath to talk about himself or his personal life, and in that he is like one of his own characters, unwilling to confuse business with pleasure.

This much he will allow: Born in 1943, he grew up in Chicago’s rough-and-tumble Humboldt Park neighborhood, where, as a teenager, he fell deeply under the spell of the burgeoning Chicago blues-music scene. He is the son of Jack Mann, a WWII combat vet whom Mann describes as “a small businessman, and not very successful at it; but he was a spectacular human being — highly, highly principled, and he affected a lot of people’s lives in a lot of ways that I don’t ever really talk about that much.” He was also close to his paternal grandfather, Sam, a Russian immigrant who had fought in the First World War, and says that both men “influenced the way I think about things. They both had dramatic lives, so the idea of some kind of sedentary, mercantile, bourgeois thing, when I was 20 or 21 years old — that was not going to happen.” Conspicuously, Mann doesn’t talk about his mother, in this or any other interviews.

Sure of what he didn’t want to do with his life, but unsure of what he did want, Mann enrolled at the politically active University of Wisconsin-Madison campus at the dawn of the turbulent 1960s. ?“I was really impacted upon by the ’60s, so the idea of real life, real people, life in the streets — that's something that's very much a part of my formation,” he says, noting that his cultural interests at the time ranged from Chicago bookies to Che Guevara; his academic ones from geology to history and architecture. Movies came later, when the Madison campus began offering its first courses in film history and film theory. Mann signed up and liked what he saw. But his real inspiration came with the 1963 release of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. “It said to my whole generation of filmmakers that you could make an individual statement of high integrity and have that film be successfully seen by a mass audience all at the same time,” he says. “In other words, you didn’t have to be making Seven Brides for Seven Brothers if you wanted to be a part of the commercial film industry, or be reduced to niche filmmaking if you wanted to be serious about cinema. So that’s what Kubrick meant, aside from the fact that I loved Kubrick and he was a big influence.”

Saved from the Vietnam draft by asthma, Mann enrolled at the London Film School, where he made “pretentious” student films he refuses to screen anymore, then segued into commercials and documentary production, funneling the money he made into more personal projects. (His 1970 experimental short film, Jaunpuri, won a prize at Cannes.) After six years, he returned to the U.S. and settled on the West Coast, landing work as a writer on Starsky and Hutch and Police Story, before being hired by the late Aaron Spelling to create the series Vega$ in 1978. His true debut came the following year with The Jericho Mile, a feature-length film for television about a Folsom prison lifer (brilliantly played by Peter Strauss) whose distance-running prowess earns him a shot at the Olympics and a rare glimpse of life beyond the jailyard walls. Shot on location with many real inmates in the cast, Jericho won three Emmys, including one for Mann and co-writer Patrick J. Nolan’s script, and it remains one of the most authentic and starkly unsentimental of prison movies. More importantly, in Strauss’ Larry “Rain” Murphy, it offered early evidence of Mann’s affinity for men of heightened self-awareness — antidotes to the Freudian psychoanalysis that is the familiar model of dramatic characterization. “I’m interested in the phenomenon of it — awareness heightened, or awareness absent, and the price you pay for either,” Mann says, in one of many concerted attempts to disabuse me of making thematic connections between his films.

His first two theatrical features, Thief (1981) and Manhunter, together with Vice on TV, announced Mann as one of the most breathtaking cinematic stylists of his era. These were gripping thrillers in which the documentary hyper-realism of Jericho was married to a feverishly beautiful graphic sensibility: dramatic colored lighting, actors framed small against great canvases of water and sky, jarring frame-rate manipulations, and long set-pieces in which dialogue was displaced by contemporary pop music. It’s impossible to discuss Mann’s work without addressing these matters of style, though Mann himself would just as soon that we not. He's suspicious of the superficiality of visual beauty, he says, and resists the “modernism” label that would make for such an easy fit (except to say that he’s “really fascinated with what’s happening right now”). But what is powerful and moving in Mann’s work (and, admittedly, rather hard to describe) is the way that style — which is to say everything that is in the frame, from the costumes to the locations to the movement of the camera itself — seems to grow out of the characters, to be expressive of something, as opposed to the vacant prettifications of Adrian Lyne or Tony Scott. I am talking about the way, in Manhunter, that the sensual caress of a blind woman’s hand against the skin of an anesthetized tiger tells us more about that woman than any dialogue possibly could; how, in Heat (1995), the flashing lights of an airport runway become a desperate, Gatsbyesque beacon; or how, in The Insider, an elaborate hotel-room mural manifests the escapist dream of the beleaguered whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand (Russell Crowe). These are images as abstract and epochal as anything in Kubrick's 2001.

“What I try to do — I mean try, because you don’t get there all the time — is to have impact with content,” Mann says. “It’s those moments in which you’re trying to bring people beyond filmed theater. If I have an ambition, it’s that. In The Insider, I had violence — lethal, life-taking aggression — all happening psychologically, all with people talking to other people. What am I making a film of?What am I shooting?What’s in the viewfinder of that camera? It’s a head, talking, in space, in a place. So then, the excitement for me as a filmmaker was the challenge of making suspense and drama involving life and death in which everything I’m shooting is only a human face. So, you start thinking about what you can do to make the places talk.”

To date, Mann’s masterpiece remains Heat, the sprawling chronicle of a career thief, Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro), planning one last score before dropping out of the game, while staying one step ahead of the dogged LAPD detective, Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino), who's intent on bringing him down. It was another story of professionalism, and one that had haunted Mann for decades: He had written the script in the 1970s, first discussed making it in the 1980s, and had directed half of it as a TV movie, L.A. Takedown, in 1989. Heat was promoted at the time as the first screen pairing of two legendary Hollywood stars and quickly immortalized for a breathtaking shootout on the streets of downtown L.A., but what was more notable about the film was the full dimensionality in which Mann envisaged nearly a dozen major characters, skirting police story clichés to show them all (cops, crooks or otherwise) in a richly human light.

“Why would their lives be less than dimensional?” he asks, as if the answer were obvious. “Of course they’re dimensional: They have mothers and fathers and kids. I knew a lot of these people, people like this. What do you have? You have a complete human being. The Tom Sizemore character: He has a nuclear family. He cares about his kids the same way you care about your kids. The big difference is that he doesn’t care about your kids: He’ll use one of your kids as a shield.”

Mann admits to being obsessive about his work: He likens himself to people who climb mountains for sport. “The next one is exciting when it’s a little bit more difficult,” he says with a grin. There is a moment from one of his films, I tell him, that I think perfectly embodies that sentiment. It is the opening scene of The Insider, in which Lowell Bergman is driven through the streets of Baalbek, Lebanon, en route to a private audience with the Hezbollah leader Sheikh Fadlallah, whom he is attempting to land for a 60 Minutes interview. The scene, which was actually filmed in Israel, might have been shot anywhere — for most of his trip, Bergman is blindfolded, and no other scene in the movie takes place in the Middle East. But then there is a shot, inside Fadlallah’s darkened compound, where Bergman throws open a window and suddenly the sights and sounds of the bustling city below stream through. That is the moment, I say, when we know we are watching a Michael Mann movie.

“You know it’s not Fontana,” Mann jokes.

He wouldn’t have it any other way. He is an iconoclast, and he prides himself on it. “That’s the thrill of doing this, to be able to go deep,” he says. “First of all, why would you not? I mean, why would anybody want to slack off, take it easy, do it at half speed? I can’t imagine why anybody would want to, when you have the opportunity, for example, to do what Will Smith did in Ali. People think, Okay, you learn to box for two or three months and then you go shoot it. Right! The accomplishment of Will Smith in that movie is extraordinary: It’s not just the movement and the boxing — that’s difficult enough; it’s having your head in 1964, which came from sitting where you’re sitting and talking to Geronimo Pratt. That’s the challenge, because that’s what’s really, sincerely exciting — to get things to the point where they become emotionalized and real, so hopefully they have an impact upon audiences.”

It sounds, I say, like the way a cop prepares to go undercover.

“That’s what knocked me out, which I’d never really realized before. I met these guys who were doing undercover work where they’re inside for six, seven, eight months — really heavy-duty stuff with very dangerous people. I’d say to them: ‘What’s the high? What are you doing this for? You’re making $100,000 a year, so it’s not about the money. It’s not to serve and protect really. I mean, of course you’re a moral person and these vicious crimes against these innocent people offend you deeply — but that’s not why you’re doing it. And this one guy says, ‘Well, when I’m there and I’m talking to some guy about how I’m going to sling this dope here and this dope there, and then we’re going to move the money from A to B and B to C and C to D and it’s going to all wind up with him owning a shopping center in Berlin, and his eyes are wide and I’m putting it down and he’s buying it and I’m scoring — man, there’s nothing like that!’ Guess what? That’s Al Pacino on a stage! That’s performance! That’s theater for real.

“These guys are projecting themselves, and they’re talking about what they do in dramaturgical terms. It’s like An Actor Prepares, only there’s no take two. If you’re a filmmaker and you’re hearing these tales . . . well, that answers your first question about why I wanted to make Miami Vice.”

In Heat’s most iconic scene, Hanna and McCauley meet for coffee at Kate Mantilini and lay out their lives for each other in the tersely lyrical dialogue that has become Mann’s signature. It includes the following exchange:

Hanna: I don’t know how to do anything else.

McCauley: Neither do I.

Hanna: I don’t much want to either.

McCauley: Neither do I.

That could just as soon be Mann talking. “When you say that I can go and make a movie, I feel like I’m one of the most fortunate men,” he says. “I feel myself to be a fortunate man that I found something to do that I really love,” The proof is in the pudding: Mann’s films are works of deep passion at a time when it is ever more fashionable to seem cool and detached. He makes big demands of audiences, but bigger ones of himself, and if that partly explains why Mann — whose movies have performed strongly, but unspectacularly at the box office — has never had a major hit, it is our good fortune that he has never given in to compromise.

As I’m leaving, he asks me how I think Miami Vice will do and I tell him that I wish it the best, but that it may be too smart of a summer movie to really take off. All that matters is that it do well enough to insure that Michael Mann can go on climbing mountains.